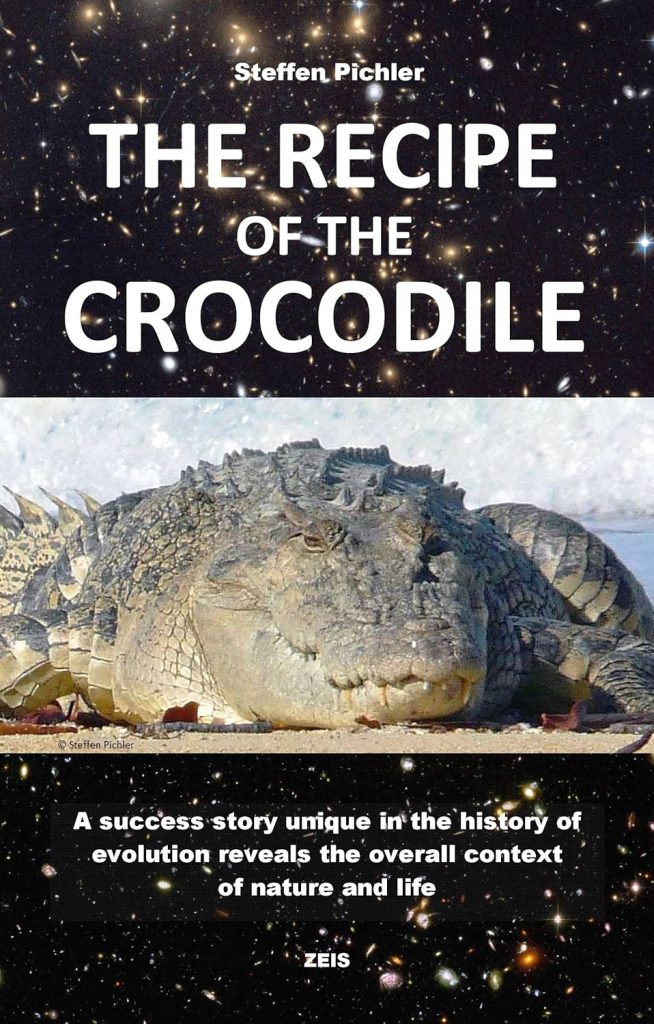

For a long time, researchers have been pondering the question of why the large life form known as the crocodile has existed at the very top of the food pyramid between water and land for more than 250 million years and has hardly changed. Now, author Steffen Pichler has finally solved the mystery: in his book „The Reciepe of the Crocodile“, he demonstrates, based on years of observation of the largest existing crocodile species and the evaluation of palaeontological studies, that the foundation of this success lies in an evolutionary adaptation towards near-perfect ‘ecological harmony’.

Pichler describes how ‘crocodiles’ did not form a ‘lineage’ in terms of life form. Rather, during the enormous period of their existence, many species emerged and disappeared which, according to palaeontological reconstructions, were often very similar but frequently only distantly related. The enormous similarities cannot therefore be explained by common ancestors. There must have been a repeated selective adaptation, which in biology is referred to as convergence. Since this concerns the oldest apex of the food pyramid at the extremely significant transition from water to land in the history of life, Pichler suspected early on that something of fundamental importance lay behind this adaptation. Through his systematic observation of free-roaming saltwater crocodiles in northern Australia, he finally found the solution: all physical and behavioural characteristics are geared towards minimising disturbance to other living creatures and positively influencing the ecosystem in a variety of ways – so comprehensively that even the best engineer would find no possibility for optimisation.

The author also uses his photographs to show how the giant reptiles become almost invisible in the sensitive shore zones of inland waters thanks to their colouring and shape, and how they glide through still water with almost no turbulence, even though they weigh a tonne. Their everyday behaviour is so reserved, calm and inconspicuous that an untrained person would not even notice their presence at first. The many positive effects range from metabolic processes that promote the microbiome of the waters, to the functions of a strict ‘health police’ through the rapid selection of diseased fish, to those of an indirect ‘protector’ of the well-established ecosystem against unsuitable intruders.

The killing of prey of any size always takes place from their free development, on average so surprisingly and quickly that a reduction in the duration of the disturbances and suffering (inevitably caused by a tip of the food pyramid) would be inconceivable in this respect as well. Pichler explains that people today usually only know crocodiles and other natural top predators from films that deliberately focus on particularly dramatic-looking scenes of prey capture, often in slow motion. This then obscures the fact that real suffering in (real) nature, away from television and YouTube, is only a marginal phenomenon and that predators in the animal kingdom are very effective at reducing prolonged suffering.

The logical selection advantage of maximum possible harmony in one’s own habitat lies, according to the pattern of mutualistic symbiosis, in the highest possible stability as the apex of the food pyramid existing therein. That is why, even when the entire land mass of the planet still consisted of the supercontinent Pangaea, life forms with the most suitable and therefore almost identical characteristics automatically moved into this particularly contested position between water and land.

In the next step, the author reflects on the crocodile as a ‘cake’ that has repeatedly fitted itself into the same ‘cake tin’. This reveals the ‘shape’ as a whole geometry of fundamental natural laws, which can be broken down and defined in a similar way to gravity or centrifugal force. They must have organised the entire ecosystem since its inception. And their further analysis leads to such deep levels of insight that logical conclusions beyond the boundaries of the space-time structure ultimately become possible.

According to Pichler, the reason why these fundamental orders of nature have not found their way into the knowledge of civilisation is that dealing with cultivated and subjugated life forms is diametrically opposed to them. This led to a collective repression of large parts of reality, and as a result, humanity was only able to develop a shallow and incomplete world view. Because this made it impossible to find a reasonable orientation, increasingly destructive and correspondingly unstable external effects arose – in contrast to the evolutionary adaptations of crocodiles. In his conclusion, the author warns that only a quick and thorough catch-up on this missed knowledge could now save humanity from destroying the rest of the Earth’s ecosystem and itself.